Abstract

We investigate the role of individual labor income as a moderator of parental subjective well-being trajectories before and after the birth of the first child in Germany. Analyzing the German Socio-Economic Panel Survey (SOEP), we found that income matters negatively for parental life satisfaction after the first birth, though with important differences by education and gender. In particular, among better educated parents, those with higher income experience a steeper decrease in their subjective well-being. Income is measured as the average of individual labor income within 3 years before the birth. We provide evidence that our results are robust to potential endogeneity between income and first childbirth using the individual labor income at 3 years from the event, and for an alternative measure, i.e. the equivalent household income. Results are discussed in terms of different aspirations and difficulties parents may experience, especially in terms of work and family balance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The role played by a family’s social and economic background, including parents’ immigrant status, on children’s educational outcomes is widely acknowledged and emerges from both cross-country and single-country studies (Ermisch and Francesconi 2001; McIntosh and Munk 2007; OECD 2010; Schüller 2015). Furthermore, there is a consensus that national educational systems and schools differ in reducing or amplifying the weight of the family background on children’s outcomes. In particular, in Germany, it appears very important the fact that the decision about which educational track children will follow is made at the early age of ten (Dustmann 2004).

In this paper, we mainly refer to life satisfaction, but we may cite papers where the focus is on “happiness”. This is standard practice among social scientists (e.g., Easterlin 2010). Subjective well-being is, in fact, a broad category, which involves positive and negative feelings, expressions of happiness, and cognitive judgments about life satisfaction (Diener and Lucas 1999). These components of subjective well-being often correlate substantially and the terms signifying its various dimensions can be used interchangeably.

Specifically, we exclude all the individuals who declare themselves non-working at least once during the observational period. As a robustness test, we provide the estimates obtained by including in the sample also non-working individuals in the Appendix. In fact, results remain almost unaffected.

This assumption does not affect our estimates since we control for labor-force status.

Clark and Georgellis (2013) put into a single equation the two equations employed by Clark et al. (2008) to separately estimate the effects on the individual level of SWB before and after a life event. As explained by the authors, estimating lags and leads jointly is the approach that correctly allows for plotting the estimated coefficients on one graph. The same is not true when the lag and lead equations are estimated separately because of different omitted categories. Myrskylä and Margolis (2014) adopt the Clark and Georgellis (2013) model, and the only differences between our model and that estimated by the former is the number and the length of the lags and leads on which the parental trajectory is built.

Ferrer-i Carbonell and Frijters (2004) show that treating life satisfaction as an ordinal variable versus a cardinal one makes little difference.

The SOEP includes a question concerning the planning of any pregnancy, but only for a sub-sample of mothers at their first childbirth, namely new mothers from 2002 onwards. These new mothers are asked whether the pregnancy was planned, unplanned, or thanks to assisted fertilization. This sub-sample includes 2035 different individuals, among whom 27% (551 individuals) declare that the pregnancy was unplanned, 71% (1445 individuals) declare that the pregnancy was planned and slightly less than 2% (39 individuals) declare that the pregnancy came after assisted fertilization. Looking at the age of these individuals, we can verify that unplanned pregnancies are concentrated among women between 20 and 30 years of age (50%), they are less frequent among women between 30 and 40 years old (42%), and quite rare for women over 40 (8%). Thus, the control on individuals’ age groups is crucial for addressing the possible bias arising from the presence of unplanned pregnancies.

Unlike those for the first child, the trajectory dummies for other parities are not mutually exclusive.

Since these calculations are very necessary to rightly interpret the results in terms of trajectory of SWB for each income group, for the sake of brevity, in Section 5, we do not show the raw estimates of Eq. 2, but instead we only provide the results of such calculations. The estimates are available upon request.

As already said in the previous footnote, the raw estimates of Eq. 2 are made available upon request.

Also in this case, we do not show the raw estimates of Eq. 2 using the individual labor income at T-3 from the birth. However, such estimate are made available upon request.

Also in this case, we do not show the raw estimates of Eq. 2 using the equivalent income. However, such estimates are made available upon request.

In our sample, the correlation between the years of education of women and the level of education of their mothers is 0.13 (significant at 1%). The correlation with the education of their fathers, meanwhile, is 0.16 (significant at 1%). Regarding men, the correlation is 0.25 (significant at 1%) with the level of education of their mothers and 0.20 (significant at 1%) with that of their fathers. Although the correlation is surely relevant, we think that this evidence does not alter our line of reasoning or the results.

Also in this case, we do not show the raw estimates of Eq. 2. However, such estimates are made available upon request.

Also in this case, we do not show the raw estimates of Eq. 2 on the sample including not-working individuals. However, such estimates are made available upon request.

References

Aassve A, Goisis A, Sironi M (2012) Happiness and childbearing across Europe. Soc Indic Res 108(1):65–86

Aassve A, Mencarini L, Sironi M (2015) Institutional change, happiness, and fertility. Eur Sociol Rev 31(6):749–765

Alger I, Cox D (2013) The evolution of altruistic preferences: mothers versus fathers. Rev Econ Househ 11(3):421–446

Andersson G (2000) The impact of labour-force participation on childbearing behaviour: pro-cyclical fertility in Sweden during the 1980s and the 1990s. European Journal of Population/Revue Européenne de Démographie 16(4):293–333

Andersson G, Kreyenfeld M, Mika T (2014) Welfare state context, female labour-market attachment and childbearing in Germany and Denmark. J Popul Res 31(4):287–316

Becker GS (1960) An economic analysis of fertility. In: Demographic and economic change in developed countries. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, pp 209–240

Becker GS (1981) Altruism in the family and selfishness in the market place. Economica 48(189):1–15

Becker GS (1991) A treatise on the family (Revised and enlarged edition). Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Becker GS, Lewis HG (1973) On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ 81(2, Part 2):S279–S288

Berninger I (2013) Women’s income and childbearing in context: First births in Denmark and Finland. Acta Sociologica 56(2):97–115

Billari FC, Kohler H-P (2009) Fertility and happiness in the XXI century: institutions, preferences, and their interactions. In: Annual meeting of the population association of America, Detroit, April 30–May 2, 2009

Blair-Loy M (2009) Competing devotions: career and family among women executives. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (2004) Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. J Public Econ 88(7):1359–1386

Boyce CJ, Wood AM (2011) Personality prior to disability determines adaptation: agreeable individuals recover lost life satisfaction faster and more completely. Psychol Sci 22(11):1397–1402

Bremhorst V, Kreyenfeld M, Lambert P (2016) Fertility progression in Germany: an analysis using flexible nonparametric cure survival models. Demogr Res 35:505–534

Brickman P (1971) Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In: Appley M (ed) Adaptation-level theory. Academic Press, New York, pp 287–305

Cetre S, Clark AE, Senik C (2016) Happy people have children: choice and self-selection into parenthood. Eur J Popul 32(3):445–473

Cigno A (1986) Fertility and the tax-benefit system: a reconsideration of the theory of family taxation. Econ J 96(384):1035–1051

Cigno A (1991) Economics of the family. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Clark AE (2016) Adaptation and the easterlin paradox. In: Advances in happiness research. Springer, pp 75–94

Clark AE, Oswald AJ (2002) A simple statistical method for measuring how life events affect happiness. Int J Epidemiol 31(6):1139–1144

Clark AE, Georgellis Y (2013) Back to baseline in Britain: adaptation in the british household panel survey. Economica 80(319):496–512

Clark AE, Diener E, Georgellis Y, Lucas RE (2008) Lags and leads in life satisfaction: a test of the baseline hypothesis. Econ J 118(529):222–243

Csikszentmihalyi M, Hunter J (2003) Happiness in everyday life: the uses of experience sampling. J Happiness Stud 4(2):185–199

Di Tella R, Haisken-De New J, MacCulloch R (2010) Happiness adaptation to income and to status in an individual panel. J Econ Behav Organ 76(3):834–852

Diener E, Lucas RE (1999) Personality and subjective well-being. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N (eds) Well-being: foundations of hedonic psychology. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp 213–229

Diener E, Lucas RE, Scollon CN (2006) Beyond the hedonic treadmill: revising the adaptation theory of well-being. Am Psychol 61(4):305–314

Duesenberry JS (1949) Income, saving, and the theory of consumer behavior. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Dustmann C (2004) Parental background, secondary school track choice, and wages. Oxf Econ Pap 56(2):209–230

Dyrdal GM, Lucas RE (2013) Reaction and adaptation to the birth of a child: a couple-level analysis. Dev Psychol 49(4):749–761

Easterlin RA (1974) Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. Nations and Households in Economic Growth 89:89–125

Easterlin RA (1995) Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? J Econ Behav Organ 27(1):35–47

Easterlin RA (2010) Well-being, front and center: a note on the Sarkozy report. Popul Dev Rev 36(1):119–124

Engelhardt H, Prskawetz A (2004) On the changing correlation between fertility and female employment over space and time. European Journal of Population/Revue Européenne de Démographie 20(1):35–62

Engelhardt H, Kögel T, Prskawetz A (2004) Fertility and women’s employment reconsidered: a macro-level time-series analysis for developed countries, 1960–2000. Popul Stud 58(1):109–120

Ermisch J, Francesconi M (2001) Family matters: impacts of family background on educational attainments. Economica 68(270):137–156

Esping-Andersen G (2013) The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Wiley, New York

Esping-Andersen G, Billari FC (2015) Re-theorizing family demographics. Popul Dev Rev 41(1):1–31

Ferrer-i Carbonell A, Frijters P (2004) How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Econ J 114(497):641–659

Frejka T (2008) Overview chapter 2: parity distribution and completed family size in europe incipient decline of the two-child family model. Demogr Res 19(14):47–72

Frey BS, Stutzer A (2000) Happiness, economy and institutions. Econ J 110(466):918–938

Goldscheider F, Bernhardt E, Lappegård T (2015) The gender revolution: a framework for understanding changing family and demographic behavior. Popul Dev Rev 41(2):207–239

Goyette KA (2008) College for some to college for all: social background, occupational expectations, and educational expectations over time. Soc Sci Res 37(2):461–484

Gregory E (2012) Ready: why women are embracing the new later motherhood. Basic Books, New York

Grossbard S, Mukhopadhyay S (2013) Children, spousal love, and happiness: an economic analysis. Rev Econ Househ 11(3):447–467

Hart RK (2015) Earnings and first birth probability among norwegian men and women 1995–2010. Demogr Res 33:1067–1104

Herbst CM, Ifcher J (2016) The increasing happiness of us parents. Rev Econ Househ 14(3):529–551

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47(2):263–292

Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N (1999) Well-being: foundations of hedonic psychology. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Kögel T (2004) Did the association between fertility and female employment within oecd countries really change its sign? J Popul Econ 17(1):45–65

Kohler H-P (2012) Do children bring happiness and purpose in life. Whither the child: causes and consequences of low fertility, pp 47–75

Kohler H-P, Behrman JR, Skytthe A (2005) Partner + children = happiness? The effects of partnerships and fertility on well-being. Popul Dev Rev 31(3):407–445

Kohler H-P, Mencarini L (2016) The parenthood happiness puzzle: an introduction to special issue. Eur J Popul 32(3):327–338

Kotowska I, Matysiak A, Pailhe A, Solaz A, Styrc M, Vignoli D (2010) Family and work. Second european quality of life survey. Dublin: Eurofond (The European Foundation for the Improvement of Living Conditions)

Kreyenfeld M, Andersson G (2014) Socioeconomic differences in the unemployment and fertility nexus: evidence from Denmark and Germany. Adv Life Course Res 21:59–73

Le Moglie M, Mencarini L, Rapallini C (2015) Is it just a matter of personality? On the role of subjective well-being in childbearing behavior. J Econ Behav Organ 117:453–475

Lesthaeghe R, Van de Kaa DJ (1986) Twee demografische transities. Bevolking: groei en krimp, pp 9–24

Lucas RE, Clark AE, Georgellis Y, Diener E (2003) Reexamining adaptation and the set point model of happiness: reactions to changes in marital status. J Pers Soc Psychol 84(3):527–539

Lucas RE, Clark AE, Georgellis Y, Diener E (2004) Unemployment alters the set point for life satisfaction. Psychol Sci 15(1):8–13

Luci A, Thevenon O (2011) Does economic development explain the fertility rebound in OECD countries. Population and Societies, INED, 481

Luci-Greulich A, Thévenon O (2014) Does economic advancement ‘cause’ a re-increase in fertility? an empirical analysis for oecd countries (1960–2007). Eur J Popul 30(2):187–221

Margolis R, Myrskylä M (2011) A global perspective on happiness and fertility. Popul Dev Rev 37(1):29–56

Matysiak A, Mencarini L, Vignoli D (2016) Work–family conflict moderates the relationship between childbearing and subjective well-being. Eur J Popul 32(3):355–379

McIntosh J, Munk MD (2007) Scholastic ability vs family background in educational success: evidence from danish sample survey data. J Popul Econ 20(1):101–120

McLanahan S, Adams J (1987) Parenthood and psychological well-being. Annu Rev Sociol 13(1):237–257

Mello ZR (2008) Gender variation in developmental trajectories of educational and occupational expectations and attainment from adolescence to adulthood. Dev Psychol 44(4):1069–1080

Myrskylä M, Kohler H-P, Billari FC (2009) Advances in development reverse fertility declines. Nature 460(7256):741–743

Myrskylä M, Kohler H-P, Billari F (2011) High development and fertility: fertility at older reproductive ages and gender equality explain the positive link. MPIDR Working Paper, 2011–017 Rostock, Germany: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research

Myrskylä M, Margolis R (2014) Happiness: before and after the kids. Demography 51(5):1843–1866

Nomaguchi KM, Brown SL (2011) Parental strains and rewards among mothers: the role of education. J Marriage Fam 73(3):621–636

Nomaguchi KM, Milkie MA (2003) Costs and rewards of children: the effects of becoming a parent on adults’ lives. J Marriage Fam 65(2):356–374

OECD (2010) PISA 2009 results: overcoming social background: equity in learning opportunities and outcomes (volume II). OECD, Paris, France

Oswald AJ (1997) Happiness and economic performance. Econ J 107(445):1815–1831

Proto E, Rustichini A (2015) Life satisfaction, income and personality. J Econ Psychol 48:17–32

Rønsen M (2004) Fertility and public policies-evidence from Norway and Finland. Demogr Res 10:143–170

Schüller S (2015) Parental ethnic identity and educational attainment of second-generation immigrants. J Popul Econ 28(4):965–1004

Sheldon KM, Lucas RE (2014) Stability of happiness: theories and evidence on whether happiness can change. Elsevier, Oxford

Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) (2016) Data for years 1984-2015, version 32, SOEP. https://doi.org/10.5684/soep.v32

Stevenson B, Wolfers J (2008) Economic growth and subjective well-being: reassessing the easterlin paradox. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research

Stone P (2007) Opting out? Why women really quit careers and head home. University of California Press, Berkeley

Tasiran AC (1995) Fertility dynamics: spacing and timing of births in Sweden and the United States. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Van de Kaa DJ (1987) Europe’s second demographic transition. Popul Bull 42 (1):1–59

Vikat A (2004) Women’s labor force attachment and childbearing in Finland. Demogr Res 3:177–212

Wagner GG, Frick JR, Schupp J (2007) The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) - Scope, Evolution and Enhancements. Schmollers Jahrbuch 127(1):139–169

Williams DE, Thompson JK (1993) Biology and behavior: a set-point hypothesis of psychological functioning. Behav Modif 17(1):43–57

Zimmermann AC, Easterlin RA (2006) Happily ever after? Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and happiness in Germany. Popul Dev Rev 32(3):511–528

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the two anonymous referees for their comments and helpful suggestions.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council, under the European ERC Grant Agreement no. StG-313617 (SWELL-FER: Subjective Well-being and Fertility).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Alessandro Cigno

Appendix: Estimates including in the sample the not-working parents

Appendix: Estimates including in the sample the not-working parents

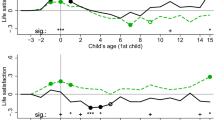

The estimates presented in Table 3 rely on a sample including both unemployed and employed individuals, but excluding all those who declare themselves not to be working. Possibly, the effect of childbirth on the level of SWB might be different for non-workers, as the decision to drop out of the labor market might be associated with a better general attitude towards parenting, and thus with a higher level of satisfaction with having a child. This could reduce the room for a generalization in the interpretation of our results. In order to address this issue, in the present section, we estimate Eq. 2 again including in the estimation sample non-working individuals. To do that, we set their individual earned income to 0 and we added a dummy to the control variables equal to 1 if the individual is not working at a given time and 0 otherwise. The trajectories by gender for each tertile of individual labor income are presented in Table 7 and plotted in Fig. 9a, b.Footnote 15 As will be noted, the decision to include non-working individuals does not affect the main results of our analysis, thus confirming the robustness of their interpretation across labor force statuses.

Mothers’ and fathers’ trajectories of subjective well-being from 3 years before up to 5 years after the birth of the first child, by tertile individual labor income (reference category of subjective well-being at time T-3). Estimations including in the sample non-working parents. Point estimates are calculated starting from the coefficients for mothers and fathers showed in columns 1 and 2 of Table 7. O, \(\square \), and X indicate significance at 10, 5, and 1%

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Le Moglie, M., Mencarini, L. & Rapallini, C. Does income moderate the satisfaction of becoming a parent? In Germany it does and depends on education. J Popul Econ 32, 915–952 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-018-0689-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-018-0689-9