Abstract

This paper studies the extent to which the job insecurity brought about by the Great Recession has had an impact on fertility decisions across Europe. My results rely not only on objective measures of job insecurity (e.g., the unemployment rate or the ratio of workers made redundant in their last job), but also on aggregate perceptions of job precariousness (e.g., the percentage of workers who say they are looking for another job because they fear they will lose their current position, or the ratio of unemployed who say they are not seeking work because they believe there is none available). Main results indicate that unemployment, long-term unemployment and the impossibility of finding a full-time job are the three indicators with the strongest link to reduced fertility over the period. However, results vary by age group, gender, and especially income, immigrant origin and country cluster. More importantly, my findings show that the Great Recession made the chances of childbearing more unequal, depending on socio-economic background.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, Morrill and Pabilonia (2015) found that couples with children in the US spent less time together during the Great Recession.

The lack of expectations and aspirations about the future brought about by an economic downturn (Giuliano and Spilimbergo 2013) has also been related to an increase in teenagers’ sexual activity (Arkes 2007; Buhi and Goodson 2007; Carpenter 2005). For the United States in the period between 2003 and 2011, Pabilonia (2017) finds that Hispanic male teenagers (aged 15–17) engage in more sexual activity during poorer economic conditions, while black male teenagers engage in less. Ananat et al. (2013) also find evidence that job losses decrease the likelihood among black teenagers of having had two or more sexual partners, and increase the probability of their using birth control.

Brooks-Gunn et al. (2013), for example, investigate the relationship between different measures of the Great Recession (unemployment, home foreclosure and an index of consumer confidence) and child maltreatment among children aged nine years and find that the loss of consumer confidence in the United States is associated with a high frequency of maternal spanking between 2007 and 2010. Moreover, the authors find the association to be particularly strong for the most advantaged groups (measured by education and household income distance to the official poverty line).

In this sense, the concept of job insecurity used in this paper differs from the concept of economic uncertainty, which mostly uses financial indicators (Comolli 2017).

Fertility cannot be studied using the EU-LFS, because age is given to researchers only in five-year intervals, and so one cannot identify a newborn child.

I study the impact of the economic environment on fertility decisions, while controlling for individual labour market status; but the aim of the paper is not to study the influence of the individual labour market status on the probability of having a child.

Analysis of the relationship between the business cycle and fertility relative to periods prior to the Great Recession includes a larger variety of countries. See, for example, Adsera and Menendez (2011) for Latin America, Andersson (2000) for Sweden, Kravdal (2002) for Norway or Kreyenfeld (2010) for Germany.

The author uses gender-education-specific shift-share indices of labour demand to instrument the unemployment rates and obtains stronger negative effects than those derived from simpler models.

The use of the longitudinal component of the EU-SILC was also considered. However, the large attrition problems of this data source (Jenkins and Van Kerm 2017) and the important differences in tracking rules across countries (Iacovou and Lynn 2013) are only two of the reasons why I disregard its use. Moreover, the cross-sectional component includes more countries and larger samples.

The use of measures relative to productivity or economic growth is beyond the scope of this paper. However, it should be noted that previous studies have suggested that indicators other than GDP better capture the impact of the business cycle on fertility (Adsera and Menendez 2011; Sobotka et al. 2011).

The individuals who left their last employment or business because a job of limited duration ended are included in the denominator of the indicator (and not in the numerator). This way, the indicator intends to capture sudden or unexpected job loss rather than the precariousness of employment, which, to my way of thinking, is already present in other indicators.

This indicator has not been used in the case of Belgium, due to large inconsistencies over time in the variable.

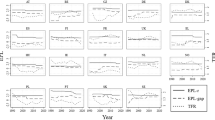

Figures A.1 and A.2 in the Supplementary Material also show the variability of the 10 indicators across the countries analysed by means of box plots and Table A.3 details the mean, maximum and minimum values of each indicator by country.

The EU-LFS indicators have been computed ignoring missing values. Moreover, I have disregarded region-year indicators if they are derived from fewer than 100 observations. For the same reason, I do not derive results by age group or gender, as they would have been drawn from too small a number of observations.

Serbia participates in the EU-SILC, but not in the EU-LFS, and so the data for this country could not be used.

NUTS is the abbreviation for Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics. There are three levels officially defined by the European Commission, with two levels of local administrative units (NUTS-1 and NUTS-2)—see an interactive map at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts.

The great majority of these cases are small countries, with the important exception of Germany.

In the analysis, twin births have been treated in the same way as singletons.

Note that exact age cannot be computed, as only the trimester of birth is reported.

Household income, in most countries, refers to t-1 and has been made equivalent using the modified OECD equivalence scale, which gives a weight of 1 to the first adult, 0.5 to all other adult members and 0.3 to children under the age of 14. The equivalence scale does not consider children born at t. The equivalent income quartiles have been defined using the whole distribution per country and year.

As explained above, for a few babies the job insecurity indicator refers to t-2, depending on the trimester when the child was born and the family interviewed. See all the details in Table A.2 in the Appendix.

Regressions without controls for labour market status (potentially endogenous) yield similar results to those presented here.

Alternatively, it could also be that, since there are only 31 countries under analysis, the number of clusters is too small to yield significant estimates at the country level (Cameron and Miller 2015).

Following the suggestion of a reviewer, I have run these main specifications while considering only those countries that have participated in the sample from 2004/2005, thus excluding those countries for which I do not have data from the beginning of the period analysed. The results are basically the same as those presented here (which serves to highlight the robustness of the latter). Also, the main results are conservative, compared to those from regressions that consider the deviation of each regional indicator from its trend (instead of the raw indicator).

As shown later, this positive relationship is mostly driven by individuals in the Mediterranean countries, where an increase in temporary work (as opposed to joblessness) may be promoting childbearing.

I would like to thank a reviewer for suggesting that I include this analysis in the paper.

Note that when statistically significant, coefficients are estimated at a very similar level as those presented in Tables 2 and 3, and are therefore not reported; however, they are available from the author on request. Moreover, results are confirmed when clustering standard errors at country level, though at different significance level.

Following the suggestion of a reviewer, I have also considered separate regressions for married individuals: the findings are similar to those presented in the previous section, albeit with stronger marginal effects.

For reasons of space, I do not show the results of analysis at the regional level using country cluster. However, all the results (also at the country level) are available from the author on request and are commented on in the text, when relevant.

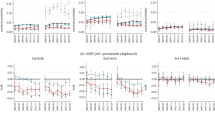

At the country level, the same relationship is found in five of the 10 indicators: unemployment, long-term unemployment, redundancy, the impossibility of finding a full-time job and the impossibility of finding a permanent one.

The analysis at country level confirms these findings, except for part-time work and the desire to work more hours.

It is important to take into account that temporary workers in Southern Europe were the first to be out of the labour market when the economy came to a sudden halt, and so the percentage of workers on a temporary contract increased only when the economy started to recover.

References

Abadie, A., Athey, S., Imbens, G. W., & Wooldridge, J. (2017). When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? Working Paper 24003, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Adsera, A. (2005). Vanishing children: from high unemployment to low fertility in developed countries. American Economic Review, 95(2), 189–193.

Adsera, A., & Menendez, A. (2011). Fertility changes in Latin America in periods of economic uncertainty. Population Studies, 65(1), 37–56.

Ananat, E. O., Gassman-Pines, A., & Gibson-Davis, C. (2013). Community-wide job loss and teenage fertility: Evidence from North Carolina. Demography, 50(6), 2151–2171.

Andersson, G. (2000). The impact of labour-force participation on childbearing behaviour: pro-cyclical fertility in Sweden during the 1980s and the 1990s. European Journal of Population, 16(4), 293–333.

Arkes, J. (2007). Does the economy affect teenage substance use? Health Economics, 16, 19–36.

Arkes, J., & Klerman, J. A. (2009). Understanding the link between the economy and teenage sexual behavior and fertility outcomes. Journal of Population Economics, 22(3), 517–536.

Becker, G. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility. In G. B. Roberts (Ed.), Demographic and economic change in developed countries (pp. 209–240). National Bureau of Economic Research, Columbia University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Becker, G. (1965). A theory of the allocation of time. Economic Journal, 75(299), 403–517.

Becker, S. O., Bentolila, S., Fernandes, A., & Ichino, A. (2010). Youth emancipation and perceived job insecurity of parents and children. Journal of Population Economics, 23(3), 1047–1071.

Bell, D. N. F., & Blanchflower, D. G. (2011). Young people and the great recession. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 27(2), 241–267.

Bellido, H., & Marcén, M. (2016). Fertility and the business cycle: the European case. Working Paper 69368, MPRA.

Ben-Porath, Y. (1973). Economic analysis of fertility in Israel: point and counter-point. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2), S202–S233.

Berghammer, C., & Sobotka, T. (2016). Falling first marriage rates in Europe during the Great Recession. A comparison of 17 countries. Paper presented at the EPC conference, Mainz, September 2016.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275.

Bredtmann, J., Otten, S., & Rulff, C. (2018). Husband’s unemployment and wife’s labor supply: the added worker effect across Europe. ILR Review, 71(5), 1201–1231.

Brooks-Gunn, J., Schneider, W., & Waldfogel, J. (2013). The great recession and the risk for child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37(10), 721–729.

Buck Louis, G. M., Lum, K. J., Sundaram, R., Chen, Z., Kim, S., Lynch, C. D., Shisterman, E. F., & Pyper, C. (2010). Stress reduces conception probabilities across the fertile window: evidence in support of relaxation. Fertility and Sterility, 95(7), 2184–2189.

Buhi, E., & Goodson, P. (2007). Predictors of adolescent sexual behavior and intention: a theory-guided systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(1), 4–21.

Burton, G. J., & Jauniaux, E. (2004). Placental oxidative stress: from miscarriage to preeclampsia. Journal of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation, 11(6), 342–352.

Butz, W. P., & Ward, M. P. (1979). The emergence of countercyclical U.S. fertility. American Economic Review, 69(3), 318–328.

Cameron, A. C., & Miller, D. (2015). A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 317–372.

Carpenter, C. (2005). Youth alcohol use and risky sexual behavior: evidence from underage drunk driving laws. Journal of Health Economics, 24(3), 613–628.

Catalano, R., Goldman-Mellor, S., Saxton, K., Margerison-Zilko, C., Subbaraman, M., LeWinn, K., & Anderson, E. (2011). The health effects of economic decline. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 431–450.

Comolli, C. L. (2017). The fertility response to the Great Recession in Europe and the United States: Structural economic conditions and perceived economic uncertainty. Demographic Research, 36, 1549–1600.

Giuliano, P., & Spilimbergo, A. (2013). Growing up in a recession. The Review of Economic Studies, 81(2), 787.

Goldstein, J., Kreyenfeld, M., Jasilioniene, A., & Orsal, D. (2013). Fertility reactions to the great recession in Europe: Recent evidence from order-specific data. Demographic Research, 29(4), 85–104.

González-Val, R., & Marcén, M. (2017). Divorce and the business cycle: a cross-country analysis. Review of Economics of the Household, 15(3), 879–904.

Iacovou, M., & Lynn, P. (2013). Implications of the EU-SILC following rules, and their implementation, for longitudinal analysis. Discussion Paper 2013-17, Institute for Economic and Social Research (ISER).

Jenkins, S., & Van Kerm, P. (2017). How does attrition affect estimates of persistent poverty rates? The case of European Union statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC). Discussion Paper, Eurostat-Statistical Working Papers.

Kravdal, O. (2002). The impact of individual and aggregate unemployment on fertility in Norway. Demographic Research, 6(10), 263–294.

Kreyenfeld, M. (2010). Uncertainties in female employment careers and the postponement of parenthood in Germany. European Sociological Review, 26(3), 351–366.

Lalive, R., & Zweimüller, J. (2009). How does parental leave affect fertility and return to work? Evidence from two natural experiments. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 1363–1402.

Levine, P. B. (2002). The impact of social policy and economic activity throughout the fertility decision tree. Discussion Paper 9021, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Lindo, J. M. (2015). Aggregation and the estimated effects of economic conditions on health. Journal of Health Economics, 40, 83–96.

Lugilde, A., Bande, R., & Riveiro, D. (2018). Precautionary saving in Spain during the great recession: evidence from a panel of uncertainty indicators. Review of Economics of the Household, 16(4), 1151–1179.

Macunovich, D. J. (1995). The Butz-Ward fertility model in the light of more recent data. Journal of Human Resources, 30(2), 229–255.

Manuelli, R. E., & Seshadri, A. (2009). Explaining international fertility differences. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(2), 771–807.

Matsudaira, J. D. (2016). Economic conditions and the living arrangements of young adults: 1960 to 2011. Journal of Population Economics, 29(1), 167–195.

Mincer, J. (1963). Market prices, opportunity costs, and income effects. In C. Christ (Ed.), Measurement in Economics: Studies in memory of Yehuda Grunfeld (pp. 67–82). Standford University Press, Stanford, California.

Morrill, M. S., & Pabilonia, S. W. (2015). What effects do macroeconomic conditions have on the time couples with children spend together? Review of Economics of the Household, 13(4), 791–814.

Nepomnaschy, P. A., Welch, K. B., McConnell, D. S., Low, B. S., Strassmann, B. I., & England, B. G. (2006). Cortisol levels and very early pregnancy loss in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103 (10), 3938–3942.

Pabilonia, S. (2017). Teenagers’ risky health behaviors and time use during the great recession. Review of Economics of the Household, 15(3), 945–964.

Schaller, J. (2016). Booms, busts, and fertility: testing the Becker model using gender-specific labor demand. Journal of Human Resources, 51(1), 1–29.

Schneider, D. (2015). The great recession, fertility, and uncertainty: evidence from the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 1144–1156.

Schneider, D., & Hastings, O. (2015). Socioeconomic variation in the effect of economic conditions on marriage and nonmarital fertility in the United States: evidence from the great recession. Demography, 52, 1893–1915.

Schneider, D., Harknett, K., & McLanahan, S. (2016). Intimate partner violence in the great recession. Demography, 53(2), 471–505.

Sobotka, T., Skirbekk, V., & Philipov, D. (2011). Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review, 37(2), 267–306.

Starr, M. A. (2014). Gender, added-worker effects, and the 2007–2009 recession: looking within the household. Review of Economics of the Household, 12(2), 209–235.

Acknowledgements

This paper has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement num. 649395, project title: NEGOTIATE—Overcoming early job-insecurity in Europe and the COST-Action CA17114. Support from the projects ECO2016-76506-4C4-R and 2017-SGR-1571 is also greatly acknowledged. Olof Bäckman (SOFI, Stockholm University) and participants at the NEGOTIATE meeting in Girona (April 2017) are thanked for their useful comments. Any errors or misinterpretations are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ayllón, S. Job insecurity and fertility in Europe. Rev Econ Household 17, 1321–1347 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-019-09450-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-019-09450-5