Abstract

Background

Manipulation of total homocysteine concentration with oral methionine is associated with impairment of endothelial-dependent vasodilation. This may be caused by increased oxidative stress. Vitamin C is an aqueous phase antioxidant vitamin and free radical scavenger. We hypothesised that if the impairment of endothelial function related to experimental hyperhomocysteinaemia was free radically mediated then co-administration of vitamin C should prevent this.

Methods

Ten healthy adults took part in this crossover study. Endothelial function was determined by measuring forearm blood flow (FBF) in response to intra-arterial infusion of acetylcholine (endothelial-dependent) and sodium nitroprusside (endothelial-independent). Subjects received methionine (100 mg/Kg) plus placebo tablets, methionine plus vitamin C (2 g orally) or placebo drink plus placebo tablets. Study drugs were administered at 9 am on each study date, a minimum of two weeks passed between each study. Homocysteine (tHcy) concentration was determined at baseline and after 4 hours. Endothelial function was determined at 4 hours. Responses to the vasoactive substances are expressed as the area under the curve of change in FBF from baseline. Data are mean plus 95% Confidence Intervals.

Results

Following oral methionine tHcy concentration increased significantly versus placebo. At this time endothelial-dependent responses were significantly reduced compared to placebo (31.2 units [22.1-40.3] vs. 46.4 units [42.0-50.8], p < 0.05 vs. Placebo). Endothelial-independent responses were unchanged. Co-administration of vitamin C did not alter the increase in homocysteine or prevent the impairment of endothelial-dependent responses (31.4 [19.5-43.3] vs. 46.4 units [42.0-50.8], p < 0.05 vs. Placebo)

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that methionine increased tHcy with impairment of the endothelial-dependent vasomotor responses. Administration of vitamin C did not prevent this impairment and our results do not support the hypothesis that the endothelial impairment is mediated by adverse oxidative stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Homocystinuria was first described in Belfast in 1962 [1], Carson et al. identified the presence of the amino acid, homocysteine, in the urine of subjects with marked skeletal abnormalities and mental retardation. It was 1969 before McCully made the association between homocysteine and vascular disease [2]. In a postmortem study of subjects with homocystinuria, and marked increase in homocysteine concentrations, he noted extensive atherosclerosis. Untreated these individuals have a high mortality before the age of 30 years, mostly from vascular and thrombotic complications [3]. More recently mild to moderate elevation of total plasma homocysteine concentration (tHcy) has become recognised as carrying an increased risk for the development of atherosclerotic vascular disease [4, 5]. The cause/effect relationship has not been fully established though, and we await the results of secondary prevention trials - investigating the effect of lowering tHcy.

Increasing evidence suggests that homocysteine promotes vascular disease through endothelial damage. In vitro, homocysteine damaged cultured endothelial cells in a dose dependent fashion [6]. In primates, dietary manipulation of tHcy resulted in endothelial damage [7] and impaired endothelial function [8]. In humans moderate elevation of tHcy was associated with impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilation before overt evidence of vascular disease [9]. In addition, experimental hyperhomocysteinaemia induced by oral methionine produced impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilation in healthy volunteers [10]. Endothelial-dysfunction is recognised as an early [11] and potentially reversible marker [12] of the atherosclerotic process. Endothelial function can be assessed by measuring changes in forearm blood flow (FBF) using venous occlusion plethysmography in response to local infusion of vasoactive substances.

These effects on the endothelium of increased tHcy may be due to free radical damage [13]. In vitro, exposing cultured endothelial cells to homocysteine results in cell damage secondary to hydrogen peroxide formation. [6] Previous studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect on endothelial function following oral vitamin C, an aqueous anti-oxidant vitamin, administration in disease states [14,15,16]. We hypothesised that if the endothelial damage in experimental hyperhomocysteinaemia were related to increased oxidative stress, then co-administration of vitamin C, an anti-oxidant vitamin, should prevent this effect.

Methods

Subjects

Ten healthy male non-smoking volunteers of mean age 23 years (range 21-25) were recruited for this study. The subjects were recruited from staff and students within our department. Each underwent a medical history, examination, ECG and routine laboratory tests. All were non-smokers with no significant past medical history of note, not on any current medications or vitamin supplements. This study was approved by the ethics committee of The Queen's University, Belfast. All subjects gave written informed consent for all procedures.

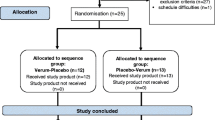

Design

Each subject was studied on three separate occasions. In a randomised fashion the subjects received oral methionine (100 mg/Kg) in fruit juice plus placebo tablets (Methionine group), methionine in fruit juice plus vitamin C tablets (Vitamin C group) and methionine-free fruit juice plus placebo tablets (Placebo group). The study employed a randomised, single (operator)-blind crossover design with a minimum of two weeks between studies.

The subjects fasted overnight and abstained from alcohol- and caffeine-containing products for 12 hours prior to the study. Randomisation took place at 9 am on each study day. Due to the distinctive taste of methionine a department technician in a room separate from the vascular laboratory performed randomisation and subjects were informed not to comment on the taste of the drink. Venous blood samples for tHcy measurement were taken and placed in ice at baseline (t = 0) and 4 hours (t = 4). FBF was assessed at 4 hours after randomisation. The brachial artery was cannulated 30 minutes prior to the first recording to allow the area to normalise.

Forearm blood flow measurements

Studies took place in a temperature-controlled room (24-26°C). A 27-gauge needle was inserted under local anaesthetic into the non-dominant brachial artery to allow local intra-arterial drug infusion. With the subject supine and the arms resting on a support slightly above the level of the heart FBF was measured by strain gauge venous occlusion plethysmography. A mercury in silastic strain gauge was coupled to an electronically calibrated plethysmograph (Medasonics model SPG16, Newark, California, USA). The voltage output was transferred to a Macintosh personal computer (Performa 630, Apple Computer Inc., Newark, California, USA) with a MacLab analog-to-digital converter and CHART software (v. 3.4.3) (AD Instruments, Hastings, UK). The mean of 5 consecutive FBF measurements was taken for statistical evaluation. FBF was expressed as ml/100 ml forearm volume/min.

Following a period of at least 30 minutes rest, during which 0.9% saline was infused, basal FBF was measured. Sodium nitroprusside was infused intra-arterially in 4 incremental doses (3, 6, 9 and 12 nmolmin-1), each for 3 minutes, to assess endothelium-independent vasodilatation with FBF measured in the last minute of each infusion. After a washout period of at least 20 minutes basal FBF was again measured. Acetylcholine was then infused intra-arterially into the experimental forearm in 4 incremental doses (60, 120, 180, 240 nmolmin-1), each for 3 minutes, to assess endothelium-dependent vasodilatation with FBF again measured in the last minute of each infusion. All infusions were administered at a rate of 1 ml/min using a constant rate infusor. The doses used have previously been shown to have no systemic effect on heart rate, blood pressure or FBF [17]. FBF was measured in both arms using the non-cannulated arm as a control to demonstrate that local vasoactive drug administration did not have a systemic action.

Plasma homocysteine

Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 950 × g for 10 min at 4°C, within 20 min of venepuncture, and stored at -70°C until analysis. Plasma tHcy was measured according to the method of Ubbink et al. [18] using HPLC with fluorescence detection. At plasma homocysteine concentration of 7.87 μmol/L the inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 6.8% with an intra-assay CV of 2.6%.

Statistical analysis

The changes in tHcy were compared using a paired sample t-test.

Basal forearm blood flow between study days was compared by use of a paired sample t-test. The responses to the vasoactive substances are expressed as the measure of area under the curve (AUC) of change in forearm blood flow from baseline, expressed in arbitrary units. This avoids making multiple comparisons [19]. Results were analysed using a paired sample t-test.

Data are expressed as mean plus 95% Confidence Intervals. Differences were considered significant at a value of p < 0.05.

Results

Following oral methionine the tHcy concentration at 4 hours increased significantly (7.5 [6.0-9.0] μmol/L vs. 22.8 [19.8-25.8] μmol/L, p < 0.0001 vs. baseline and Placebo, Table 1). Co-administration of vitamin C did not significantly alter the rise in tHcy (7.6 [6.2-9.0] μmol/L vs. 21.6 [18.3-24.9] μmol/L, p < 0.0001 vs. Baseline and Placebo, Table 1). There was no change in basal tHcy between study dates suggesting no carry over effect.

Basal FBF was similar in each group suggesting low intra-experimental variation (Table 1), and basal FBF was unchanged prior to each drug infusion (data not shown). FBF in the control arm did not change in response to infusion of any study drug thus confirming that the drug effects were confined to the experimental forearm (data not shown).

Following oral methionine the AUC of change in endothelial-dependent FBF from baseline was significantly reduced compared to placebo, (31.2 arbitrary units [22.1-40.3] vs.46.4 arbitrary units [42.0-50.8] vs. p < 0.05 vs. Placebo, Figures 1 &2, Table 1). Co-administration of vitamin C did not alter this reduction compared to placebo (31.4 [19.5-43.3] arbitrary units vs. 46.4 [42.0-50.8] arbitrary units, p < 0.05 vs. Placebo, Figures 1 &2, Table 1). The mean difference in AUC between the methionine and vitamin C groups emphasises the lack of difference these groups (0.2 [-15.9-16.3]) arbitrary units, Table 1).

The endothelial-independent responses were similar in the placebo (22.0 [16.7-27.3] arbitrary units), methionine (22.2 [13.1-31.3] 22.2 [13.1-31.3] arbitrary units) and vitamin C groups (21.6 [18.7-24.5] arbitrary units), and there was no significant difference between groups (Figure 1).

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that oral methionine (100 mg/Kg) increased tHcy concentration significantly at t = 4 hours. This increase was associated with reduced endothelial-dependent FBF compared to the placebo group. However, co-administration of vitamin C (2 g orally), an aqueous phase anti-oxidant, did not alter the increase in tHcy nor prevent the impairment of endothelial-dependent FBF responses.

Mild to moderated elevation in tHcy is associated with an increased risk for the development of vascular disease [4, 5, 20], yet whether homocysteine is causal remains to be completely proven. There are also several negative studies with regard to homocysteine and vascular disease. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study [21] was a prospective trial that and showed that there was no overall association between tHcy and coronary artery disease. Also, the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) [22] failed to demonstrate any association between tHcy and the development of myocardial infarction. Overall though the balance of evidence supports the theory that increased tHcy is associated with increased vascular risk. In a recent meta-analysis Danesh and Lewington [23] demonstrated that there was an overall association between elevated tHcy and coronary heart disease. This association was greatest for the retrospective studies with odds ratio of 1.9 (1.6 - 2.3, 95% CI), while the association from prospective trials was 1.3 (1.1 - 1.5) and for the retrospective population controlled studies 1.6 (1.4 - 1.7). We await the results of the secondary prevention trials that will look at the effect of lowering tHcy (mostly folic acid based regimes) on vascular risk; these trials are currently ongoing and will help clarify the issue.

Increasingly evidence suggests that homocysteine exerts its vascular effect by promoting endothelial damage. Moderate elevation in tHcy was associated with impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilation in adults without overt evidence of vascular disease [9] and dietary manipulation of tHcy in primates induced impairment of endothelial function. [8] This is important, as impairment of endothelial function is an early and reversible marker of the atherogenic process [11, 12].

To investigate the possible mechanisms involved in this process attention has focused on the effects of experimental hyperhomocysteinaemia. Chambers et al. [10] then Bellamy et al. [24] demonstrated acute impairment of endothelial-dependent dilation following methionine-induced (100 mg/Kg) hyperhomocysteinaemia in healthy volunteers. We have confirmed these findings though using a different technique to assess endothelial function. [25] We also demonstrated that the changes were most likely due to the increase in tHcy, and not methionine. We have also previously shown that a much lower concentration of methionine (250 mg orally), had no effect on tHcy or endothelial-dependent vasodilation. Also in an open study of eight volunteers we demonstrated that methionine (100 mg/Kg) for 7 days was associated with increased tHcy but there was no impairment of endothelial-dependent vasodilation [26].

There are different ways to assess endothelial function. Briefly, flow mediated dilatation [10, 24] measures the change in brachial artery diameter, using an ultrasound probe. Following a period of arterial occlusion, the increased flow (shear forces) stimulates endothelial-dependent vasodilation. This method assesses conduit vessel responses. Our method [17, 25] measures the change in forearm blood flow using venous occlusion plethysmography following the local, intra-arterial infusion of vasoactive substances. This method assesses resistance vessel function.

There is some evidence to suggest that homocysteine damages the endothelium by increased oxidative stress. We hypothesised that if the adverse effect on endothelial-dependent function was due to increased oxidative stress then co-administration with vitamin C should prevent this effect. Vitamin C, or ascorbic acid, is the main water-soluble anti-oxidant in human plasma and is an effective scavenger of reactive oxygen species. Previous studies have demonstrated that vitamin C reversed endothelial vasomotor impairment in-patients with coronary artery disease, [14] chronic cigarette smoking [16] and hypercholesterolaemia [15].

Chambers and colleagues [27] have reported that administration of vitamin C (1 g/day for 7 days) prevented the impairment of conduit vessel endothelial-dependent dilation associated with experimental hyperhomocysteinaemia. Kanani et al. [28] investigated the effect of methionine-induced hyperhomocysteinaemia on conduit and resistance vessel endothelial function. In a similar number of subjects and similar protocol to our study, both authors demonstrated that vitamin C prevented the impairment of endothelial-dependent vasodilation. Our data are at conflict with the published material. We could not demonstrate that vitamin C attenuated the effects of experimental hyperhomocysteinaemia on endothelial function when studying resistance vessels, and our data do not support the theory that the changes are due to increased oxidative stress.

There are several possible reasons for our negative results, as with any negative study involving small number of subjects, the possibility of a Type II error is raised. We feel that as the FBF results in the methionine and vitamin C group are so similar and the mean difference between the groups is zero, the possibility of a Type II error is unlikely. In addition we used similar design and sample size to the published data. Another possibility is that the vitamin C levels were not sufficient to produce an effect. Again this is unlikely as this dose has been previously validated, we chose 2 g of ascorbic acid orally, administered at the same time as the methionine; this dose is known to increase plasma ascorbate concentrations 2.5-fold, with stable concentrations from 2 to 5 hours after dosing. [14] Another possibility is that publication bias has resulted in under-representation of negative results.

On closer inspection of the published data there are several inconsistencies. The data from Chambers et al. [27] revealed that administration of vitamin C did not completely prevent the impairment of endothelial-dependent dilation following oral methionine. In the placebo group endothelial-dependent stimulation resulted in brachial artery dilation (4.3 ± 1.0%), following methionine this dilatation was significantly impaired (-0.7 ± 0.8%), while in the methionine plus vitamin C group the artery dilated 2.8 ± 0.7%. So in this group there was some dilation, and vitamin C only slightly attenuated the impairment. Their data clearly showed an outlying response that had a major influence on the mean value, in favour of the vitamin C treatment. Therefore we are unclear if the authors have in fact demonstrated a significant effect. In the paper by Kanani et al. [28] the authors demonstrated an effect in a similar number to our study. They demonstrated clearly that administration of vitamin C completely prevented the impairment of endothelial-dependent vasodilation as assessed by flow-mediated dilatation (conduit vessel) and venous occlusion plethysmography following intra-arterial infusion (resistance vessel). It is unclear from the paper how the authors were able to accurately measure brachial artery diameter responses when there was a cannula in the artery.

Recent work questions whether increased oxidative stress does play a role in homocysteine induced vascular disease [29]. If oxidative stress due to hyperhomocysteinaemia plays a role in vascular damage then one might reasonably expect to detect markers of oxidant stress in the sera from subjects with homocystinuria, and markedly increased tHcy. This has not been the case however. LDL isolated from subjects with homocystinuria, and marked elevation of tHcy, was not more susceptible to oxidation than control LDL [30]. Markers of lipid peroxidation were no higher in the serum of subjects than controls [31, 32]. A more recent study, however, using a more sensitive marker of oxidative damage did suggest a correlation between tHcy and increased lipid peroxidation (as assessed by F2 isoprostane concentration) [33].

In conclusion, we have been unable to confirm that vitamin C affects endothelial function in experimental hyperhomocysteinaemia. Our results therefore do not support the hypothesis that methionine induced impairment of endothelial-dependent vasodilation was mediated by increased oxidant stress.

References

Carson NAJ, Neill DW: Metabolic abnormalities detected in a survey of mentally backward individuals in Northern Ireland. Arch Disease Child. 1962, 37: 505-513.

McCully KS: Vascular pathology of homocysteinemia: implications for the pathogenesis of arteriosclerosis. Am J Path. 1969, 56: 111-128.

Wilcken DE, Wilcken B: The natural history of vascular disease in homocystinuria and the effects of treatment. J Inh Metab Dis. 1997, 20: 295-300. 10.1023/A:1005373209964.

Graham IM, Daly LE, Refsum HM, Robinson K, Brattstrom LE, Ueland PM, Palma-Reis RJ, Boers GH, Sheahan RG, Israelsson B, et al: Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease. The European Concerted Action Project. JAMA. 1997, 277: 1775-1781. 10.1001/jama.277.22.1775.

Clarke R, Daly L, Robinson K, Naughten E, Cahalane S, Fowler B, Graham I: Hyperhomocysteinemia: an independent risk factor for vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1991, 324: 1149-1155.

Starkebaum G, Harlan JM: Endothelial cell injury due to copper-catalyzed hydrogen peroxide generation from homocysteine. JCI. 1986, 1370-1376.

Harker LA, Harlan JM, Ross R: Effect of sulfinpyrazone on homocysteine-induced endothelial injury and arteriosclerosis in baboons. Circ Research. 1983, 53: 731-739.

Lentz SR, Sobey CG, Piegors DJ, Bhopatkar MY, Faraci FM, Malinow MR, Heistad DD: Vascular dysfunction in monkeys with diet-induced hyperhomocyst(e)inemia. JCI. 1996, 98: 24-29.

Tawakol A, Omiand T, Gerhard M, Wu JT, Creager MA: Hyperhomocyst(e)inemia is associated with impaired endothelium- dependent vasodilation in humans. Circulation. 1997, 95: 1119-1121.

Chambers JC, McGregor A, Jean-Marie J, Kooner JS: Acute hyperhomocysteinaemia and endothelial dysfunction. Lancet. 1998, 351: 36-37.

Ross R: The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993, 362: 801-809. 10.1038/362801a0.

Harrison DG, Armstrong ML, Freiman PC, Heistad DD: Restoration of endothelium-dependent relaxation by dietary treatment of atherosclerosis. JCI. 1987, 80: 1808-1811.

Loscaizo J: The oxidant stress of hyperhomocyst(e)inemia. JCI. 1996, 98: 5-7.

Levine GN, Frei B, Koulouris SN, Gerhard MD, Keaney JFJ, Vita JA: Ascorbic acid reverses endothelial vasomotor dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1996, 93: 1107-1113.

Ting HH, Timimi FK, Haley EA, Roddy MA, Ganz P, Creager MA: Vitamin C improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in forearm resistance vessels of humans with hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1997, 95: 2617-2622.

Heitzer T, Just H, Munzel T: Antioxidant vitamin C improves endothelial dysfunction in chronic smokers. Circulation. 1996, 94: 6-9.

McVeigh GE, Brennan GM, Johnston GD, McDermott BJ, McGrath LT, Henry WR, Andrews JW, Hayes JR: Impaired endothelium-dependent and independent vasodilation in patients with type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1992, 35: 771-776.

Ubbink JB, Hayward VW, Bissbort S: Rapid high-performance liquid chromatographic assay for total homocysteine levels in human serum. J Chromat. 1991, 565: 441-446. 10.1016/0378-4347(91)80407-4.

Matthews JN, Altman DG, Campbell MJ, Royston P: Analysis of serial measurements in medical research. BMJ. 1990, 300: 230-235.

Stampfer MJ, Malinow MR, Willett WC, Newcomer LM, Upson B, Ullmann D, Tishler PV, Hennekens CH: A prospective study of plasma homocyst(e)ine and risk of myocardial infarction in US physicians. JAMA. 1992, 268: 877-881. 10.1001/jama.268.7.877.

Evans RW, Shaten BJ, Hempel JD, Cutler JA, Kuller LH: Homocyst(e)ine and risk of cardiovascular disease in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Arterio Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997, 17: 1947-195.

Folsom AR, Nieto FJ, McGovern PG, Tsai MY, Malinow MR, Eckfeldt JH, Hess DL, Davis CE: Prospective study of coronary heart disease incidence in relation to fasting total homocysteine, related genetic polymorphisms, and B vitamins: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 1998, 98: 204-210.

Danesh J, Lewington S: Plasma homocysteine and coronary heart disease:systematic review of published epidemiological studies. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1998, 5;: 229-232.

Bellamy MF, McDowell IF, Ramsey MW, Brownlee M, Newcombe RG, Lewis MJ: Hyperhomocysteinemia after an oral methionine load acutely impairs endothelial function in healthy adults. Circulation. 1998, 98: 1848-1852.

Hanratty CG, McAuley DF, McGrath LT, Young IS, Johnston GD: The effects of oral methionine and homocysteine on endothelial function. Heart. 2001, 85: 236-240. 10.1136/heart.85.3.326.

Hanratty CG, McAuley DF, McGurk C, Young IS, Johnston GD: Homocysteine and endothelial vascular function. Lancet. 1998, 351: 1288-1289.

Chambers JC, McGregor A, Jean-Marie J, Obeid OA, Kooner JS: Demonstration of rapid onset vascular endothelial dysfunction after hyperhomocysteinemia: an effect reversible with vitamin C therapy. Circulation. 1999, 99: 1156-1160.

Kanani PM, Sinkey CA, Browning RL, Allaman M, Knapp HR, Haynes WG: Role of oxidant stress in endothelial dysfunction produced by experimental hyperhomocyst(e)inemia in humans. Circulation. 1999, 100: 1161-1168.

Jacobsen DW: Hyperhomocysteinaemia and oxidative stress. Time for a reality check?. Arterio Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000, 20: 1182-1184.

Blom HJ, Kleinveld HA, Boers GH, Demacker PN, Hak-Lemmers HL, MT TP-P, Trijbels JM: Lipid peroxidation and susceptibility of low-density lipoprotein to in vitro oxidation in hyperhomocysteinaemia. Eur J din Invest. 1995, 25: 149-154.

Blom HJ, Engelen DP, Boers GH, Stadhouders AM, Sengers RC, de Abreu R, TePoele-Pothoff MT, Trijbels JM: Lipid peroxidation in homocysteinaemia. J Inh Metab Dis. 1992, 15: 419-422.

Dudman NP, Wilcken DE, Stocker R: Circulating lipid hydroperoxide levels in human hyperhomocysteinemia. Relevance to development of arteriosclerosis. Arterios Thromb. 1993, 13: 512-516.

Voutilainen S, Morrow JD, Roberts LJ, Alfthan G, Alho H, Nyyssonen K, Salonen JT: Enhanced in vivo lipid peroxidation at elevated plasma total homocysteine levels. Arterio Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999, 19: 1263-1266.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/backmatter/1471-2261-1-1-b1.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Have you in the past five years received reimbursements, fees, funding, or salary from an organisation that may in any way gain or lose financially from the publication of this paper? NO

Do you hold any stocks or shares in an organisation that may in any way gain or lose financially from the publication of this paper? NO

Do you have any other financial competing interests? NO

Are there any non-financial competing interests you would like to declare in relation to this paper? NO

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanratty, C.G., McGrath, L.T., McAuley, D.F. et al. The effect on endothelial function of vitamin C during methionine induced hyperhomocysteinaemia. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 1, 1 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-1-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-1-1