Abstract

Background

The present study analyses the relation between smoking status and the parameters used to assess vascular structure and function.

Methods

This cross-sectional, multi-centre study involved a random sample of 1553 participants from the EVIDENT study. Measurements: The smoking status, peripheral augmentation index and ankle-brachial index were measured in all participants. In a small subset of the main population (265 participants), the carotid intima-media thickness and pulse wave velocity were also measured.

Results

After controlling for the effect of age, sex and other risk factors, present smokers have higher values of carotid intima-media thickness (p = 0.011). Along the same lines, current smokers have higher values of pulse wave velocity and lower mean values of ankle-brachial index but without statistical significance in both cases.

Conclusions

Among the parameters of vascular structure and function analysed, only the IMT shows association with the smoking status, after adjusting for confounders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A consistent relationship has been demonstrated between cigarette smoke exposure and the progression of carotid atherosclerosis [1], with a strong positive association with coronary artery calcium burden [2]. Smoking has been associated with increased arterial stiffness and central hemodynamic indices [3–6]. There is evidence that the ankle-brachial index inversely and linearly correlates with cigarette smoking [7, 8]. Nevertheless, when evaluating vascular structure and function, every test has different accessibility and costs [9]. Several authors have proposed that the patient’s age, sex, blood pressure and heart rate, and the presence of obesity, diabetes and vascular drugs, are the main determinants of the parameters that assess arterial stiffness and vascular function [10–13]. The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between smoking status and vascular structure and function in a random sample of the adult population from the EVIDENT study.

Methods

Study design and population

The EVIDENT study is a cross-sectional and multi-centre study of six patient groups distributed throughout Spain. Participants, aged 20–80 years, were selected by stratified random sampling. The following exclusion criteria were applied: known coronary or cerebrovascular atherosclerotic disease, heart failure, moderate or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, walking-limiting musculoskeletal disease, advanced respiratory, renal or hepatic disease, severe mental disease, treated oncological disease diagnosed in the past 5 years and terminal illness. The study was approved by an independent ethics committee from Salamanca University Hospital (Spain), and all participants provided written informed consent according to the general recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki. The recruitment and data collection were conducted between 2011 and 2012. A total of 1553 individuals were included in the study. The sample size calculation indicated that this number was sufficient to detect a difference of 5 units in the peripheral augmentation index between 3 smoking statuses (i.e., smoker, former smoker and non-smoker) in a two-sided test, assuming a common standard deviation (SD) of 21 units with a significance level of 95% and a power of 90%. The IMT and PWV were measured in only 265 participants, but this number was sufficient to detect a 0.05 mm difference in the IMT between the 3 groups, assuming a SD of 0.1, a significance level of 95% and a power of 80%. The findings presented in this manuscript are a subanalysis of the EVIDENT study, the main results of which were recently published [14].

Variables and measurement instruments

Smoking history was assessed by asking questions about the participant’s smoking status. For the analyses, the participants were classified as non-smokers, former (>1 year without smoking) or present smokers. Carotid ultrasonography to assess intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery (C-IMT) was performed with the Sonosite Micromax ultrasound device (Sonosite Inc., Bothell, Washington, USA) paired with a 5–10 MHz multi-frequency high-resolution linear transducer. Sonocal software was used to perform automatic IMT measurements. Six measurements were performed on each carotid artery using average values (average IMT) and maximum values (maximum IMT) automatically calculated by the software. The measurements were taken following the recommendations of the Manheim Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Consensus [15]. Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV) was estimated using the SphygmoCor System (AtCor Medical Pty Ltd., Head Office, West Ryde, Australia), according to the expert consensus document on arterial stiffness by Van Bortel et al. [16]. The central blood pressure and radial or peripheral augmentation index (PAIx) were measured with the Pulse Wave Application Software (A Pulse) (HealthSTATS International, Singapore) using tonometry to capture the radial pulse and to estimate the central blood pressure using a patented equation. The PAIx was calculated as follows: (second peak systolic blood pressure [SBP2] - diastolic blood pressure [DBP])/ (first peak SBP - DBP) × 100 (%). The PAIx was standardised to a heart rate of 75 bpm. The ankle-brachial index (ABI) was measured using a portable WatchBP Office ABI (Microlife AG Swiss Corporation). The ABI was calculated automatically dividing the higher of the two ankle systolic pressures by the highest measurement of the two systolic pressures in the arm [17]. All measurements (IMT, PWV, PAIx75 and ABI) were performed in the morning. Smoking was not allowed within the 3 h prior to the measurements. Further details on the EVIDENT study design have been published elsewhere [18].

Statistical analysis

Statistical normality was checked using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, while non-normally distributed variables were presented as median and 75–25th percentile. Frequency distribution was used for the categorical variables. The difference in means in continuous variables between the smoking categories was analysed using a one-way analysis of variance for independent samples and the post-hoc Scheffé contrast, with alpha <0.05 and the Kruskal–Wallis test when the variables were not normal. Chi-squared tests were used to compare the differences in categorical variables.

Age, sex, blood pressure, heart rate, and the presence of obesity, diabetes and vascular drugs have shown to affect the PWV, IMT or augmentation index values. Therefore, it is necessary to control the effect of these variables in the relationship between smoking status and the parameters of vascular structure and function. To analyse the relationship between the vascular structure and function (IMT, PAIx75, PWV or ABI) and smoking status (non-smoker = 0, present smoker = 1, former smoker =2), a general linear model (GLM) analysis was performed, including age, sex, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, body mass index, HDL cholesterol, diabetes and the presence of antihypertensive, antidiabetic and lipid-lowering drugs as the adjustment variables. The non-normal variables were modelled as continuous variables with log transformation to achieve normality in the multivariate analysis. Data were analysed using the SPSS version 18.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA), and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the clinic characteristics of each group according to its smoking status. Current smokers are younger and have the lowest prevalence of hypertension, obesity and dyslipidemia. PWV, IMT and ABI are lower in present smokers, while PAIx75 are higher in these individuals. An analysis of the 265 individuals for whom the IMT and PWV were performed is shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. The results showed that the demographic and biological characteristics, according to smoking status, were similar to the overall analysed sample. The mean package year in the present smokers was 16.78 ± 16.31, and the average smoking history was 30.39 ± 12.57 years. In an age-adjusted correlation, we found a positive correlation between the package years and the PAIx75 (r = 0.332, p = 0.015) and a negative correlation with the ABI (r = -289; p = 0.036). The PWV and IMT showed no significant correlations.

Table 2 shows the IMT, PWV, PAIx75 and ABI values according to patient sex; the presence of diabetes, antihypertensive, antidiabetic and lipid-lowering drugs. IMT and PWV are higher in the male participants, diabetics and patients undergoing vascular treatment. The PAIx 75 shows the highest values in females, individuals with diabetes and patients undergoing vascular treatments, while the ABI shows differences in individuals with and without diabetes.

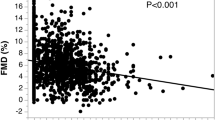

Table 3 shows a bivariate correlation between systolic blood pressure, heart rate and body mass index with each vascular structure and functional parameter (i.e., PWV, IMT, PAIx75 and ABI) analysed. Age shows a linear relationship with PWV, IMT and PAIx75 (Figure 1).

After controlling for the effects of age, sex, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, body mass index, HDL-cholesterol, diabetes and the presence of antihypertensive, antidiabetic and lipid-lowering drugs, the multivariate analysis shows that present smokers have higher IMT values (p = 0.011). PWV behaves likewise, although it does not reach the level of statistical significance. ABI has no modifications, and PAIx75 has higher values in current smokers than in former smokers (Figure 2). More details of the multivariate analysis are shown in Table 2 of the Additional file 2: (Table S2).

Relationship between the smoking status, vascular structure and function parameters adjusted by age, sex, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, body mass index, HDL cholesterol, diabetes and the presence of antihypertensive, antidiabetic and lipid-lowering drugs. Figure represents the adjusted means and 95% CI. Statistical significance: IMT p = 0.011*, PWV p = 0.872, PAIx75 p = 0.150, ABI p = 0.464.

Discussion

In this paper, we present data about the relationship between smoking status and a large variety of parameters that assess vascular structure and function in a general population sample from primary care clinics. To assess vascular structure and function, parameters differ in their relationships with cardiovascular risk factors. The results of this work show that IMT is the parameter that best relates to smoking status in a representative sample of adult population. After controlling for the effects of sex and other confounders, present smokers have higher mean IMT values (p = 0.011), while the differences in PWV, PAIx75 and ABI did not reach the level of statistical significance.

The study results concerning the effects of smoking status on subclinical arterial disease align with those of other authors [1, 2], indicating that smoking relates to the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis in an adult population. Some authors have reported that smoking aligned with increased inflammatory markers [19, 20]. Other authors have shown that the polymorphism -930A/G may modify the association between smoking and IMT values, particularly among healthy young adults [21]. We found no correlation between the mean package years in present smokers with IMT. This result can be explained by the small number of present smokers for whom the IMT was analysed.

After controlling for confounders, we found no association between the presence of smoking and increased arterial stiffness. In a systematic literature review, Doonan RJ et al. [22] found that some studies found no significant difference in the arterial stiffness between non-smokers and long-term smokers; they concluded that the effect of smoking on arterial stiffness remains to be established by prospective smoking cessation trials. Rhee et al. found an association between PWV and cigarette smoking in male smokers with hypertension. Their study explored the acute effects of smoking in a sample of men with and without hypertension, while our work examined the chronic effects of smoking on a larger sample of the Spanish general population. Other differences between the study of Rhee and Kubozono [3, 4] and our work are the different variables used in the multiple regression models. Age and SBP [10] are among the major determinants of PWV. In our study, the smoker group was the youngest and had lower SBP values. Although these variables were included in the multivariate analysis model, it may not be sufficient to control the effects that they may have on the study results.

Previous studies have demonstrated an association between AIx and cardiovascular risk factors, including smoking [6, 23]. In our work, the highest BMI corresponds to the former smokers group, which could explain the lower value of PAIx75 in this group because the augmentation index decreases when BMI increases [24]. Among the major determinants of PAIx75 are the patient age, SBP and BMI. In our study, the smoking group had the youngest participants and lower SBP and BMI levels. Although these two variables were included in the multivariate analysis, they may not sufficiently counteract the effects of other variables in the study. Furthermore, Janner JH et al. and Minami J et al. [6, 23] analysed the relationship of smoking with CAIx, while in our work we use the radial or peripheral augmentation index. Radial and central AIx are not interchangeable in the clinical practice, although the radial augmentation index has been established as a marker of vascular aging [25].

Present smokers have lower ABI values, similar to the results of other authors [7, 26]. However, our results did not remain significant after adjusting for confounders. The study population of Lee YH et al. [26] was from the general population with a mean age of 65 and 70 years in subjects with and without peripheral arterial disease, respectively. The peripheral arterial disease is one of the major manifestations of generalised atherosclerotic disease, as a result of progressive atherosclerosis [27]; therefore, it is expected that individuals with longer smoking histories will have lower ABI values. The population studied in our work has a lower median age (52.9 ± 13 years), with the youngest members in the smoking group.

The main limitation of this study is the cross-sectional design that prevents the establishment of causal relationships between smoking and vascular structure and function. The participants of the three smoking categories differed in terms of age and the prevalence of other risk factors. This limitation is, to some extent, addressed by the statistical analysis that controls the effect of these variables in the interpretation of results. Another limitation of this study is that the smoking status was self-reported and not determined by objective measures, such as CO in the expired air analysis; however, such questionnaires have been used previously in other studies to explore the relationship between arterial stiffness and smoking [5]. Lastly, a full set of data (IMT and PWV) are only available in a small subset of the EVIDENT study. However, this sample has similar demographic and biological characteristics, according to smoking status, compared to the overall sample analysed.

Conclusions

Among the parameters vascular structure and function analysed, only the IMT shows association with the smoking status, after adjusting for confounders. Further studies focusing on the smoking statuses of participants are necessary to clarify the role of the chronic effects of smoking on the parameters of vascular structure and function and the effects of passive smoking exposure.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PAIx75:

-

Peripheral or radial augmentation index adjusted for heart rate at 75 bpm

- ABI:

-

Ankle brachial index

- IMT:

-

Intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery

- PWV:

-

Pulse wave velocity.

References

Howard G, Wagenknecht LE, Burke GL, Diez-Roux A, Evans GW, McGovern P, Nieto FJ, Tell GS: Cigarette smoking and progression of atherosclerosis: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. JAMA. 1998, 279 (2): 119-124. 10.1001/jama.279.2.119.

Jockel KH, Lehmann N, Jaeger BR, Moebus S, Mohlenkamp S, Schmermund A, Dragano N, Stang A, Gronemeyer D, Seibel R, et al: Smoking cessation and subclinical atherosclerosis–results from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. Atherosclerosis. 2009, 203 (1): 221-227. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.041.

Kubozono T, Miyata M, Ueyama K, Hamasaki S, Kusano K, Kubozono O, Tei C: Acute and chronic effects of smoking on arterial stiffness. Circ J. 2011, 75 (3): 698-702. 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0552.

Rhee MY, Na SH, Kim YK, Lee MM, Kim HY: Acute effects of cigarette smoking on arterial stiffness and blood pressure in male smokers with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2007, 20 (6): 637-641. 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.12.017.

Mahmud A, Feely J: Effect of smoking on arterial stiffness and pulse pressure amplification. Hypertension. 2003, 41 (1): 183-187. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000047464.66901.60.

Janner JH, Godtfredsen NS, Ladelund S, Vestbo J, Prescott E: The association between aortic augmentation index and cardiovascular risk factors in a large unselected population. J Hum Hypertens. 2012, 26 (8): 476-484. 10.1038/jhh.2011.59.

Cui R, Iso H, Yamagishi K, Tanigawa T, Imano H, Ohira T, Kitamura A, Sato S, Shimamoto T: Relationship of smoking and smoking cessation with ankle-to-arm blood pressure index in elderly Japanese men. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006, 13 (2): 243-248. 10.1097/01.hjr.0000209818.36067.51.

Hennrikus D, Joseph AM, Lando HA, Duval S, Ukestad L, Kodl M, Hirsch AT: Effectiveness of a smoking cessation program for peripheral artery disease patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 56 (25): 2105-2112. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.031.

Gomez-Marcos MA, Gonzalez-Elena LJ, Recio-Rodriguez JI, Rodriguez-Sanchez E, Magallon-Botaya R, Munoz-Moreno MF, Patino-Alonso MC, Garcia-Ortiz L: Cardiovascular risk assessment in hypertensive patients with tests recommended by the European guidelines on hypertension. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012, 19 (3): 515-522. 10.1177/1741826711401981.

Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: ‘establishing normal and reference values’. Eur Heart J. 2010, 31 (19): 2338-2350.

Recio-Rodriguez JI, Gomez-Marcos MA, Patino-Alonso MC, Agudo-Conde C, Rodriguez-Sanchez E, Garcia-Ortiz L: Abdominal obesity vs general obesity for identifying arterial stiffness, subclinical atherosclerosis and wave reflection in healthy, diabetics and hypertensive. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012, 12: 3-10.1186/1471-2261-12-3.

Garcia-Ortiz L, Garcia-Garcia A, Ramos-Delgado E, Patino-Alonso MC, Recio-Rodriguez JI, Rodriguez-Sanchez E, Gomez-Marcos MA: Relationships of night/day heart rate ratio with carotid intima media thickness and markers of arterial stiffness. Atherosclerosis. 2011, 217 (2): 420-426. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.03.037.

Lee HY, Oh BH: Aging and arterial stiffness. Circ J. 2010, 74 (11): 2257-2262. 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0910.

Garcia-Ortiz L, Recio-Rodriguez JI, Puig-Ribera A, Lema-Bartolome J, Ibanez-Jalon E, Gonzalez-Viejo N, Guenaga-Saenz N, Agudo-Conde C, Patino-Alonso MC, Gomez-Marcos MA: Blood pressure circadian pattern and physical exercise assessment by accelerometer and 7-day physical activity recall scale. Am J Hypertens. 2013, Epub ahead of print

Touboul PJ, Hennerici MG, Meairs S, Adams H, Amarenco P, Bornstein N, Csiba L, Desvarieux M, Ebrahim S, Fatar M: Mannheim carotid intima-media thickness consensus (2004–2006). An update on behalf of the Advisory Board of the 3rd and 4th Watching the Risk Symposium, 13th and 15th European Stroke Conferences, Mannheim, Germany, 2004, and Brussels, Belgium, 2006. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007, 23 (1): 75-80. 10.1159/000097034.

Van Bortel LM, Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Chowienczyk P, Cruickshank JK, De Backer T, Filipovsky J, Huybrechts S, Mattace-Raso FU, Protogerou AD, et al: Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens. 2012, 30 (3): 445-448. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834fa8b0.

Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Murphy WR, Olin JW, Puschett JB, et al: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Associations for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease)--summary of recommendation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006, 17 (9): 1383-1397. 10.1097/01.RVI.0000240426.53079.46. quiz 1398

Garcia-Ortiz L, Recio-Rodriguez JI, Martin-Cantera C, Cabrejas-Sanchez A, Gomez-Arranz A, Gonzalez-Viejo N, Iturregui-San Nicolas E, Patino-Alonso MC, Gomez-Marcos MA: Physical exercise, fitness and dietary pattern and their relationship with circadian blood pressure pattern, augmentation index and endothelial dysfunction biological markers: EVIDENT study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10: 233-10.1186/1471-2458-10-233.

Casula M, Tragni E, Zambon A, Filippi A, Brignoli O, Cricelli C, Poli A, Catapano AL: C-reactive protein distribution and correlation with traditional cardiovascular risk factors in the Italian population. Eur J Intern Med. 2013, 24 (2): 161-166. 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.09.010.

Asthana A, Johnson HM, Piper ME, Fiore MC, Baker TB, Stein JH: Effects of smoking intensity and cessation on inflammatory markers in a large cohort of active smokers. Am Heart J. 2010, 160 (3): 458-463. 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.06.006.

Fan M, Raitakari OT, Kahonen M, Juonala M, Hutri-Kahonen N, Porsti I, Viikari J, Lehtimaki T: The association between cigarette smoking and carotid intima-media thickness is influenced by the -930A/G CYBA gene polymorphism: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Am J Hypertens. 2009, 22 (3): 281-287. 10.1038/ajh.2008.349.

Doonan RJ, Hausvater A, Scallan C, Mikhailidis DP, Pilote L, Daskalopoulou SS: The effect of smoking on arterial stiffness. Hypertens Res. 2010, 33 (5): 398-410. 10.1038/hr.2010.25.

Minami J, Ishimitsu T, Ohrui M, Matsuoka H: Association of smoking with aortic wave reflection and central systolic pressure and metabolic syndrome in normotensive Japanese men. Am J Hypertens. 2009, 22 (6): 617-623. 10.1038/ajh.2009.62.

Maple-Brown LJ, Piers LS, O'Rourke MF, Celermajer DS, O'Dea K: Central obesity is associated with reduced peripheral wave reflection in indigenous Australians irrespective of diabetes status. J Hypertens. 2005, 23 (7): 1403-1407. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000173524.80802.5a.

Heffernan KS, Patvardhan EA, Kapur NK, Karas RH, Kuvin JT: Peripheral augmentation index as a biomarker of vascular aging: an invasive hemodynamics approach. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012, 112 (8): 2871-2879. 10.1007/s00421-011-2255-y.

Lee YH, Shin MH, Kweon SS, Choi JS, Rhee JA, Ahn HR, Yun WJ, Ryu SY, Kim BH, Nam HS, et al: Cumulative smoking exposure, duration of smoking cessation, and peripheral arterial disease in middle-aged and older Korean men. BMC Public Health. 2011, 11: 94-10.1186/1471-2458-11-94.

Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Manolio TA, Polak J, Fried LP, Borhani NO, Wolfson SK: Ankle-arm index as a marker of atherosclerosis in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Cardiovascular Heart Study (CHS) Collaborative Research Group. Circulation. 1993, 88 (3): 837-845. 10.1161/01.CIR.88.3.837.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2261/13/109/prepub

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by Castilla y León Health Service (SAN/1778/2009), Carlos III Institute of Health of the Ministry of Health of Spain (PS09/00233, PS09/01057, PS09/01972, PS09/01376, PS09/0164, PS09/01458, RETICS RD12/0005/0004) and the Infosalud Foundation.

EVIDENT group members

Coordinating centre: Luis Garcia Ortiz, Manuel A Gómez Marcos, José I Recio Rodriguez and Carmen Patino Alonso of the Primary Care Research Unit of La Alamedilla Health Centre, Salamanca, Spain.

Participating centres: La Alamedilla Health Center, Servicio de Salud de Castilla y León SACYL: Carmen Castaño Sánchez, Carmela Rodriguez Martín, Yolanda Castaño Sánchez, Cristina Agudo Conde, Emiliano Rodriguez Sánchez, Luis J Gonzalez Elena, Carmen Herrero Rodriguez, Benigna Sánchez Salgado, Angela de Cabo Laso and Jose A Maderuelo Fernández.

Passeig de Sant Joan Health Centre, Servicio de Salud Catalan: Carlos Martín Cantera, Joan Canales Reina, Epifania Rodrigo de Pablo, Maria Lourdes Lasaosa Medina, Maria Jose Calvo Aponte, Amalia Rodriguez Franco, Elena Briones Carrio, Carme Martin Borras, Anna Puig Ribera and Ruben Colominas Garrido.

Poble Sec Health Centre, Servicio de Salud Catalan: Juanjo Anton Alvarez, Mª Teresa Vidal Sarmiento, Ángela Viaplana Serra, Susanna Bermúdez Chillida, Aida Tanasa.

Ca N’Oriac Health Centre, Servicio de Salud Catalan: Montserrat Romaguera Bosch.

Sant Roc Health Centre, Servicio de Salud Catalan: Maria Mar Domingo, Anna Girona, Nuria Curos, Francisco Javier Mezquiriz, Laura Torrent.

Cuenca III Health Centre, Servicio de Salud de Castilla-La Mancha SESCAM: Alfredo Cabrejas Sánchez, María Teresa Pérez Rodríguez, María Luz García García, Jorge Lema Bartolomé and Fernando Salcedo Aguilar.

Casa de Barco Health Centre, Servicio de Salud de Castilla y León SACYL: Carmen Fernandez Alonso, Amparo Gómez Arranz, Elisa Ibáñez Jalón, Aventina de la Cal de la Fuente, Laura Muñoz Beneitez, Natalia Gutiérrez, Ruperto Sanz Cantalapiedra, Luis M Quintero Gonzalez, Sara de Francisco Velasco, Miguel Angel Diez Garcia, Eva Sierra Quintana and Maria Cáceres.

Torre Ramona Health Centre, Servicio de Salud de Aragon: Natividad González Viejo, José Felix Magdalena Belio, Luis Otegui Ilarduya, Francisco Javier Rubio Galán, Amor Melguizo Bejar, Cristina Inés Sauras Yera, Mª Jesus Gil Train, Marta Iribarne Ferrer and Miguel Angel Lafuente Ripolles.

Primary Care Research Unit of Bizkaia, Basque Health Service-Osakidetza: Gonzalo Grandes, Alvaro Sanchez, Nahia Guenaga, Veronica Arce, Maria SoledadArietaleanizbealoa, Eguskiñe Iturregui San Nicolás, Rosa Amaia Martín Santidrián and Ana Zuazagoitia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author’s declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

JIR devised the study, designed the protocol, assisted with fund raising and results interpretation, prepared the draft of the manuscript and corrected the final version of the manuscript. MAG, CM, EI and AM participated in the study design, results interpretation, and manuscript review. CA participated in the study design, data collection and manuscript review. MCP performed all analytical methods, results interpretation, and manuscript review. LG participated in the protocol design, fund raising, analysis of results, and final review of the manuscript. Finally, all authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12872_2013_644_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Table S1: Characteristics of patients by smoking status in the 265 subjects for whom the IMT and the PWV was assessed. (DOC 56 KB)

12872_2013_644_MOESM2_ESM.doc

Additional file 2: Table S2: Multivariate analysis of structure and function vascular parameters with smoking status (GLM). (DOC 40 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Recio-Rodriguez, J.I., Gomez-Marcos, M.A., Patino Alonso, M.C. et al. Association between smoking status and the parameters of vascular structure and function in adults: results from the EVIDENT study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 13, 109 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-13-109

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-13-109