Abstract

Background

Isolated, asymptomatic first degree AV block with narrow QRS has not prognostic significance and is not usually treated with pacemaker implantation. In some cases, yet, loss of AV synchrony because of a marked prolongation of the PR interval may cause important hemodynamic alterations, with subsequent symptoms of heart failure. Indeed, AV synchrony is crucial when atrial systole, the "atrial kick", contributes in a major way to left ventricular filling, as in case of reduced left ventricular compliance because of aging or concomitant structural heart disease.

Case presentation

We performed a trans-septal left atrium catheterization aimed at evaluating the entity of a mitral valve stenosis in a 72-year-old woman with a marked first-degree AV block, a known moderate aortic stenosis and NYHA class III symptoms of functional deterioration. We occurred in a deep alteration in cardiac hemodynamics consisting in an end-diastolic ventriculo-atrial gradient without any evidence of mitral stenosis. The patient had a substantial improvement in echocardiographic parameters and in her symptoms of heart failure after permanent pacemaker implantation with physiological AV delay.

Conclusion

We conclude that if a marked first degree AV block is associated to instrumental signs or symptoms of heart failure, the restoration of an optimal AV synchrony, achieved with dual-chamber pacing, may represent a reasonable therapeutic option leading to a consequent clinical improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Loss of atrio-ventricular (AV) synchrony due to first-degree AV block may cause important hemodynamic alterations, with subsequent decrease in cardiac output and symptoms of heart failure. Indeed, AV synchrony is crucial when atrial systole contributes in a major way to left ventricular (LV) filling, as in case of reduced LV compliance because of aging or concomitant structural heart disease. We present the case of a patient with first degree AV block, associated with aortic valve disease, who received an evident clinical benefit by sequential pacing despite having refused aortic valve replacement as a first-line therapeutic option.

Case presentation

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our Catheterization Laboratory for an invasive re-evaluation of her NYHA class III heart failure symptoms. Three months before she had received, at a different Institution, the echocardiographic diagnosis of moderate aortic and apparently trivial mitral stenosis, despite severe valve calcification, with mild LV hypertrophy (wall thickness was 13 mm) and good systolic function. A pharmacological regimen, consisting in enalapril and furosemide, both 20 mg a day, had been established; despite medical therapy she kept complaining of effort dyspnea. ECG (figure 1) had revealed a first degree AV block, PR interval measuring 290 milliseconds, with normal QRS duration.

She underwent left and right cardiac catheterization with trans-septal access to the left atrium. Coronary arteries and regional LV systolic function were angiographically normal. LV ejection fraction was 0.65, cardiac index was 2.6 L/min/m2 and aortic and pulmonary systolic pressure were 130 and 38 mmHg, respectively. Aortic stenosis was confirmed to be moderate (the ventricle-to-aorta gradient was 50 mmHg at catheter pullback and aortic valve area was calculated to be 1.0 cm2). At fluoroscopy the mitral annulus was heavily calcified, but there was no hemodynamic evidence of mitral stenosis. With the trans-septal technique, moreover, we demonstrated (figure 2) that atrial contraction prematurely occurred soon after mitral valve opening, as shown on the left atrial tracing by the a wave(corresponding to atrial systole) falling very close to the preceding y wave(corresponding to early-diastolic unloading of the atrium into the ventricle). The high and prominent v waveconsequently represented marked pressure elevation and reduced compliance of both left atrium and ventricle. Furthermore, LV filling pressure was as increased by the preceding atrial contraction as to cause a 6-mmHg end-diastolic ventriculo-atrial gradient that was evident, at the time of the R wave on the ECG, between the x wave(corresponding to the atrial relaxation not followed by a properly timed ventricular contraction) and the LV pressure tracing.

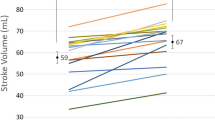

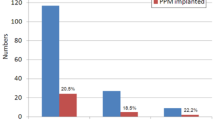

We discussed with the patient the therapeutic options [1]: she preferred to defer aortic valve replacement, whereas accepted to undergo permanent pacing. We performed an echocardiographic evaluation of systolic and diastolic function before pacemaker implantation (Table 1). Of note, the functional deterioration could be explained by the evidence of a grade II diastolic dysfunction[2]: transmitral flow was showing a high-velocity (150 cm/s) single filling wave with a deceleration time of 155 ms. Dual-chamber pacemaker implantation with optimal restoration of AV synchrony (programmed AV delay 150 ms) resulted in clinical improvement up to NYHA class II on the same medications. Since both sinus node function and atrial sensing were satisfying, ventricular pacing was triggered by P wave with a QRS duration of 120 ms [3–5]. The echocardiographic evaluation 2 days after pacemaker implantation showed a reduction of both diastolic dysfunction[2] to grade I (pattern of abnormal relaxation with an E/A ratio of 0.6) and pulmonary artery systolic pressure to 28 mmHg, whereas cardiac output appeared to be slightly improved (Table 1) despite the depletive effect of furosemide could have kept the systolic performance lower than expected in such a hypertrophied, non-enlarged left ventricle with aortic stenosis. The patient is now under close echocardiographic monitoring for the optimal timing of aortic valve replacement.

Conclusion

Isolated, asymptomatic first degree AV block with narrow QRS has not prognostic significance[6] and is not usually treated with pacemaker implantation in clinical practice. Yet, a hemodynamic condition similar to that of pacemaker syndrome [7–10] may occur when a marked first-degree AV block compromises the physiological sequence of events in the cardiac cycle[11]. Indeed, either, with longer PR intervals atrial, contraction takes place during the preceding ventricular systole against closed AV valves[7, 10] or, with less long PR intervals, it falls during the early or the mid ventricular diastole, shortening the diastolic period itself and creating an abnormal ventriculo-atrial gradient[11], as in the present case, possibly leading to reversal diastolic AV flow, provided that LV pressure is higher than atrial one during atrial relaxation[9, 12, 13]. Anyway, the hemodynamic consequences are an increase in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and a related decrease in cardiac output. Such changes, indeed, are especially harmful both in case of LV systolic[9, 14–16] and diastolic (as in the present case) dysfunction and may be, at least in part, antagonized with permanent pacemaker implantation[17, 18]. Thus, a properly timed atrial contraction, the "atrial kick", is necessary for optimal LV systolic function by increasing LV end-diastolic pressure while maintaining a low mean left atrial pressure[11].

We conclude that if a marked first degree AV block is associated to instrumental signs or symptoms of heart failure, the restoration of an optimal AV synchrony, achieved by dual-chamber pacing and despite permanent right ventricular stimulation[4, 5], may represent a reasonable therapeutic option leading to a consequent clinical improvement.

Abbreviations

- AV:

-

atrio-ventricular

- LV:

-

left ventricular

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association

References

Carabello BA: Evaluation and management of patients with aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2002, 105 (15): 1746-1750. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000015343.76143.13.

Galderisi M: Diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic aspects. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2005, 3 (1): 9-10.1186/1476-7120-3-9.

Rediker DE, Eagle KA, Homma S, Gillam LD, Harthorne JW: Clinical and hemodynamic comparison of VVI versus DDD pacing in patients with DDD pacemakers. Am J Cardiol. 1988, 61 (4): 323-329. 10.1016/0002-9149(88)90938-1.

Leclercq C, Gras D, Le Helloco A, Nicol L, Mabo P, Daubert C: Hemodynamic importance of preserving the normal sequence of ventricular activation in permanent cardiac pacing. Am Heart J. 1995, 129 (6): 1133-1141. 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90394-1.

Maurer DE, Naegeli B, Straumann E, Bertel O, Frielingsdorf J: Quality of life and exercise capacity in patients with prolonged PQ interval and dual chamber pacemakers: a randomized comparison of permanent ventricular stimulation vs intrinsic AV conduction. Europace. 2003, 5 (4): 411-417. 10.1016/S1099-5129(03)00087-4.

Mymin D, Mathewson FA, Tate RB, Manfreda J: The natural history of primary first-degree atrioventricular heart block. N Engl J Med. 1986, 315 (19): 1183-1187.

Kim YH, O'Nunain S, Trouton T, Sosa-Suarez G, Levine RA, Garan H, Ruskin JN: Pseudo-pacemaker syndrome following inadvertent fast pathway ablation for atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1993, 4 (2): 178-182.

Prech M, Grygier M, Mitkowski P, Stanek K, Skorupski W, Moszynska B, Zerbe F, Cieslinski A: Effect of restoration of AV synchrony on stroke volume, exercise capacity, and quality-of-life: can we predict the beneficial effect of a pacemaker upgrade?. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001, 24 (3): 302-307. 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.t01-1-00302.x.

de Gregorio C, Recupero A, Cento D, Coglitore S: [Reversal left diastolic ventriculo-atrial flow induced by asynchronism in a patient with dilated cardiopathy and VVI pacemaker]. G Ital Cardiol. 1999, 29 (1): 81-85.

Ellenbogen KA, Thames MD, Mohanty PK: New insights into pacemaker syndrome gained from hemodynamic, humoral and vascular responses during ventriculo-atrial pacing. Am J Cardiol. 1990, 65 (1): 53-59. 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90025-V.

Nishimura RA, Hayes DL, Holmes DRJ, Tajik AJ: Mechanism of hemodynamic improvement by dual-chamber pacing for severe left ventricular dysfunction: an acute Doppler and catheterization hemodynamic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995, 25 (2): 281-288. 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00419-Q.

Panidis IP, Ross J, Munley B, Nestico P, Mintz GS: Diastolic mitral regurgitation in patients with atrioventricular conduction abnormalities: a common finding by Doppler echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986, 7 (4): 768-774.

Schnittger I, Appleton CP, Hatle LK, Popp RL: Diastolic mitral and tricuspid regurgitation by Doppler echocardiography in patients with atrioventricular block: new insight into the mechanism of atrioventricular valve closure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988, 11 (1): 83-88.

Reiter MJ, Hindman MC: Hemodynamic effects of acute atrioventricular sequential pacing in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. 1982, 49 (4): 687-692. 10.1016/0002-9149(82)91947-6.

Brecker SJ, Xiao HB, Sparrow J, Gibson DG: Effects of dual-chamber pacing with short atrioventricular delay in dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 1992, 340 (8831): 1308-1312. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92492-X.

Auricchio A, Sommariva L, Salo RW, Scafuri A, Chiariello L: Improvement of cardiac function in patients with severe congestive heart failure and coronary artery disease by dual chamber pacing with shortened AV delay. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1993, 16 (10): 2034-2043.

Hochleitner M, Hortnagl H, Hortnagl H, Fridrich L, Gschnitzer F: Long-term efficacy of physiologic dual-chamber pacing in the treatment of end-stage idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1992, 70 (15): 1320-1325. 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90769-U.

Auricchio A, Klein H: Dual-chamber pacing in dilated cardiomyopathy: insufficient sample size, heterogeneous population and inappropriate end point may lead to erroneous conclusions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996, 27 (6): 1548-1549. 10.1016/S0735-1097(96)90107-2.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2261/5/23/prepub

Acknowledgements

GA has been admitted to the PhD course in "Cardiovascular Imaging" at the University of Messina, Italy and has received a Grant by the Italian Society of Cardiology for a Fellowship in Interventional Cardiology at the Department of Cardiac Surgery of the Tor Vergata University of Rome, Italy.

Written consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FV and GA carried out the catheterization procedure. FV coordinated the clinical management of the patient whereas GA prepared, edited and reviewed the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ando', G., Versaci, F. Ventriculo-atrial gradient due to first degree atrio-ventricular block: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 5, 23 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-5-23

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-5-23